As explained in earlier posts, this series is based on reading some online material by Thomas PM Barnett, his recent blog posts, some articles, and book descriptions. I haven’t read the books, and would be interested in reactions from anyone who has. Links to some of what I’ve read are to be found in the earlier posts, and more links are in the final postscript below.

This is the last in the series.

There are points in Thomas PM Barnett’s writing where the main impression is one of arrogance. The basic premise of it being imperative for Core states to expand globalisation throughout Gap states, by force if necessary, seems at odds with principles of self-determination, of national sovereignity, at odds with proud histories of independence struggles throughout the post-colonial world. That TPM Barnett suggests a continuity between 19th and 20th Century imperialism and 21st Century globalisation doesn’t help, nor does his focus on nation states rather than populations and individuals. With a rationale of focusing on strategy and leaving tactics to others he gives the impression of an impersonal, uncaring, unprincipled, amoral and inhumane view of the world.

Yet the aim of his grand project is humane and moral - an end to war through the expansion of economic interdependence, and along the way a fight against poverty, against disease, and against the murderous fanaticism that thrives in the Gap.

Much of what I’ve read of his writing - granted a small portion of the total - seems derived from two cases: The threat that emerged from an isolated, underdeveloped, Taliban-ruled Afghanistan, and China’s success to date in integrating a undemocratic state into the global economy. The result is a theory which sees global development as the United States’ primary strategy against external threats, and regards the promotion of democracy and universal human rights as of lesser importance, even as a potential threat to the primary strategy.

To play the naming game, one might characterise TPM Barnett as a neo-realist, someone who regards certain principles as appropriate to be set aside in pursuit of victory. There are a number of differences between this neo-realist and the old-school realists of the Cold War. TPM Barnett has a different enemy in view, he does not view containment as strategically viable, (though I presume it remains a tactical option,) and he doesn’t define success as victory for the American nation, but as victory for the American economic system.

I think the downgrading of democracy and universal human rights in all this is an error, and a strategic error as well as a moral one.

An undemocratic leadership can’t claim a legal mandate for its actions, as whatever law it follows is not accountable to the population. So however much the population may participate in economic development, the legal status of much of that development will be in doubt. Sustainable economic globalisation depends on having a stable legal basis on which to operate.

An undemocratic leadership is able to plunder national wealth with impunity, in which case economic benefit will no longer serve to maintain the support of the population, and as repression can only achieve so much then some other unifying idea is needed, popular choices being nationalism, racism, religion, class warfare, and so-called anti-imperialism. None of these is amenable to deeper global economic integration. (TPM Barnett seems to see economic benefits in religion, but I am unconvinced. If some religions appear to have greater economic benefit than others, this suggests to me that perhaps it isn’t the religious aspect of the religions that are beneficial, but cultural aspects of those particular religions.)

As TPM Barnett places contemporary economic globalisation (Globalisation III in his terminology) in a narrative that begins with 19th and 20th Century colonial imperialism (Globalisation I) and continues with the Cold War period (Globalisation II), I think it’s worth considering the issue of democracy and universal human rights in connection with the failures of those earlier periods of globalisation.

The empires of Globalisation I proved unsustainable as whatever economic benefit they may have brought colonised populations were outweighed by demand for national liberation, while undemocratic client states of Globalisation II were vulnerable to extreme corruption, political violence, and totalitarian ideology sold under the brand of anti-imperialism. Most of the problems of the Gap states, from the prime example of Afghanistan on, are legacies of the failures in Globalisation I and II to see democracy and universal human rights as essential elements in sustainable global economic integration.

Where they continue to follow the models of Globalisation I and II, the current governments of Russia and China hinder the success of Globalisation III. I have in mind not just the invasion of Georgia, and the Russian government’s attempt to maintain a sphere of influence through economic and military threats, but also its unhelpful semi-alliance with Iran, and in the case of the Chinese government, its dealings with Sudan.

In emphasising the need for economic development to combat violent political extremism, TPM Barnett would seem to be in line with contemporary military counter-insurgency thinking, but counter-insurgency theory sees the population as the territory, not the state leadership. When TPM Barnett allows his strategic viewpoint to restrict him to seeing the world in terms of nation states, he loses sight of populations and the complexities of their motivations. Those motivations are more complex than pure economics, as illustrated by the fact that Al Qaeda emerged from wealthy Saudi Arabia.

As I understand it, successful counter-insurgency depends not just on military force and economic development, but on empowering populations by providing military security, political power, economic development, open communications, and legal accountability. All are essential and interdependent, and any prioritisation is tactical and temporary.

While TPM Barnett’s writing has much to offer, his Core and Gap model seems too crude and too shallow to me. The future of the world is not just in the hands of its current leaders. With advancing communications, populations are more powerful than ever, and their world is not so neatly divided by borders between nation states, much less by TPM Barnett’s border between Core and Gap.

Postscript one: Globalisation 55 BC

Thomas PM Barnett begins the story of globalisation with 19th Century colonial imperialism. Joseph Conrad looks back even farther. His Heart of Darkness opens not in the Congo, but in the mouth of the Thames, as darkness falls and friends in a boat wait for the turning of the tide. It is one of these, Marlow, who has the tale to tell. Before talking of African colonies, however, he speculates on the Romans who came empire-building to Britain.

‘And this also’ said Marlow suddenly, ‘has been one of the dark places of the earth.’He continues -

‘I was thinking of very old times, when the Romans first came here, nineteen hundred years ago - the other day . . . Light came out of this river since - you say Knights? Yes; but it is like a running blaze on a plain, like a flash of lightning in the clouds. We live in the flicker - may it last as long ass the old earth keeps rolling! But darkness was here yesterday. Imagine the feelings of a commander of a fine - what d’ye call ’em? - trireme in the Mediterranean, ordered suddenly to the north; run overland across the Gauls in a hurry; put in charge of one of these craft the legionaries - a wonderful lot of handy men they must have been, too - used to build, apparently by the hundred, in a month or two, if we may believe what we read. Imagine him here - the very end of the world, a sea the colour of lead, a sky the colour of smoke, a kind of ship about as rigid as a concertina - and going up this river with stores, or orders, or what you like. Sand-banks, marshes, forests, savages - precious little to eat fit for a civilized man, nothing but Thames water to drink. No Falernian wine here, no going ashore. Here and there a military camp lost in the wilderness, like a needle in a bundle of hay - cold, fog, tempests, disease, exile, and death - ’

There is more, speculation about other Romans, the decent young citizen come north to mend his fortunes after too much dice, feeling the utter savagery of alien Britain closing round him, the mystery ‘in the forest, in the jungles, in the hearts of wild men.’

‘He has to live in the midst of the incomprehensible, which is also detestable. And it has a fascination too, that goes to work upon him. The fascination of the abomination - you know, imagine the growing regrets, the longing to escape, the powerless disgust, the surrender, the hate.’

How to survive such a challenge? Marlow continues, expressing first a criticism of Rome that he later makes of Europe’s ventures in Africa, a charge that today’s anti-imperialists level at globalisation, that the venture is purely one of narrow self-interest.

‘They were no colonists; their administration was merely a squeeze, and nothing more, I suspect. They were conquerors, and for that you want only brute force - nothing to boast of, when you have it, since your strength is just an accident arising from the weakness of others. They grabbed what they could get for the sake of what was to be got. It was robbery with violence, aggravated murder on a great scale, and men going at it blind as is very proper for those who tackle a darkness. The conquest of the earth, which mostly means the taking it away from those who have a different complexion or slightly flatter noses than ourselves, is not a pretty thing when you look into it too much. What redeems it is the idea only. An idea at the back of it; not a sentimental pretence but an idea; an unselfish belief in the idea - something you can set up, and bow down before, and offer a sacrifice to . . .’

The question of idealism versus rapaciousness, and of how much of the idealistic rhetoric of colonialism was sincere, is a theme that runs through Heart of Darkness. The character with the highest ideals in the book is Kurtz, and it is he who falls farthest as his belief in his own words carries him beyond the boundaries of civilisation. Well, perhaps they were the wrong ideals. Heart of Darkness becomes increasingly vague as Conrad and his alter ego Marlow approach the book’s subject.

At the time Conrad wrote that the Romans were ‘no colonists’ he couldn’t know how short-lived Europe’s empires of the time would be compared with Rome’s over four centuries of rule in England. Even so, their ideas lasted longer than their rule, so his emphasis on the idea holds. There is a parallel here with TPM Barnett’s notion of success being victory for American ideas rather than for the American nation.

Postscript two: These Romans are crazy

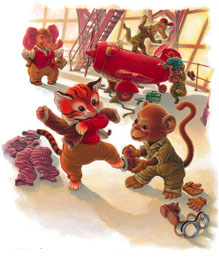

The most important texts on Roman imperialism are of course the Asterix books written by René Goscinny and drawn by Albert Uderzo, set in the year 50 BC and concerning a small village of indomitable Gauls resisting Roman rule. Of these, Obelix & Co. from 1976 is particularly relevant to economic globalisation as a counter-insurgency strategy, telling of how Julius Caesar’s adviser Caius Preposterous, fresh out of the Latin School of Economics, tries to conquer the Gaulish village, not through force of arms but by engaging them in trade.

Caius starts buying menhirs from Asterix’s best friend Obelix, introducing the Gaul to the concept of currency and encouraging him to expand his business by employing other villagers in order to step up production. Some villagers are jealous of Obelix’s success and set up menhir production businesses in competition with him. For a time the strategy is a success as Gaulish attacks on Romans cease, all of them being too busy making money, and Caius markets the menhirs as luxury goods in Rome allowing him to turn a profit - but not for long.

Caius obviously wasn’t a good student at the LSE as his strategy leads to a menhir bubble as Roman producers enter the market, undercutting the price of imported Gaulish menhirs. The result is a financial crisis as the Imperial Treasury is overexposed in menhirs when the bubble bursts. Even worse, Obelix loses interest in business when he finds that there isn’t much interesting to spend his money on, Caius having overlooked the option of exporting desirable goods to the Gaulish village. Finally, Obelix’s village competitors are furious when they discover the market for their menhirs has evaporated, and as they haven’t diversified their businesses they instead go back to bashing Romans. In the romantic, anti-imperialist, anti-urban world of Asterix and Obelix, happiness is staying in the Gap.

One shouldn’t think from this that Goscinny was always a reflexive anti-establishment satirist. My favourite story of his is the Lucky Luke version of Jesse James, drawn by Morris. In it he takes apart the fantasy of Jesse James as Robin Hood. In his version Jesse is inspired by Robin of Sherwood to take up crime, but once he has his hands on some loot is troubled by the notion giving it to the poor. His brother Frank has the solution: they take it in turns to be poor so they can pass their swag back and forth, keeping it in the family.

Postscript three: Related links

A collection of reactions to Tom Barnett, mainly with regard to his comments on the Russian invasion of Georgia, gathered by blogger Fabius Maximus. I haven’t had time to follow all of them.

Some Barnett blog posts on preferring market-led economic penalties over military responses to Russian actions in Georgia: By all means vote with your dollars, August 14th, Hit ’em where they is, August 28, Georgia ‘opportunity’ cost: $8B, September 4th, Russian backlash adds up, September 15th, More evidence, September 18th.

More Barnett on Russia: The limits of authoritarianism, and Putin’s limits, September 25th. Barnett sees rule of law as essential, but seems to regard economic consequences as the best corrective for unlawful rule, not democratic accountability.

Some Barnett posts on democracy: Some truly bad thinking, August 4th, and Immature democracies are dangerous, August 19th - note the article linked to in that post cites a death toll figure very much out of date. Finally from August 20th a post praising an article by Spengler in Asia Times Online, Americans play Monopoly, Russians chess, which begins:

On the night of November 22, 2004, then-Russian president - now premier - Vladimir Putin watched the television news in his dacha near Moscow. People who were with Putin that night report his anger and disbelief at the unfolding ‘Orange’ revolution in Ukraine. “They lied to me,” Putin said bitterly of the United States. “I’ll never trust them again.” The Russians still can’t fathom why the West threw over a potential strategic alliance for Ukraine. They underestimate the stupidity of the West.And further on continues:

The Russians know (as every newspaper reader does) that Georgia’s President Mikheil Saakashvili is not a model democrat, but a nasty piece of work who deployed riot police against protesters and shut down opposition media when it suited him - in short, a politician in Putin's mold. America’s interest in Georgia, the Russians believe, has nothing more to do with promoting democracy than its support for the gangsters to whom it handed the Serbian province of Kosovo in February.Again, the Russians misjudge American stupidity. Former president Ronald Reagan used to say that if there was a pile of manure, it must mean there was a pony around somewhere. His epigones have trouble distinguishing the pony from the manure pile. The ideological reflex for promoting democracy dominates the George W Bush administration to the point that some of its senior people hold their noses and pretend that Kosovo, Ukraine and Georgia are the genuine article.

Charming.

A rather more enjoyable article Barnett linked to: Babble Rouser, a Forbes piece on Denis O’Brien, a mobile phone entrepeneur specialising in developing countries, from the August 11th issue.

On neocons versus realists, neo or otherwise, Barnett linked disapprovingly to this piece by Robert Kagan from the Wall Street Journal of August 30th on Russia and Georgia, and on contemporary realists and neoconservatives. The comments on Barnett’s post lead me to a Newsweek article by Fareed Zakaria on Obama, ‘the true realist’, July 19th, and Who’s more realistic: McCain or Obama? from September 14th.

A couple of recent related articles not linked to by Barnett: from the IHT, Polish foreign minister Radoslaw Sikorski on negotiating the missile defence deal, September 23rd, and on Russia’s challenge to European strategic thinking, September 26th.

Also, the BBC’s Bridget Kendall interviews Mikhail Saakashvili, September 27th. He too points to the economic consequences for Russia, which he asserts were much worse than those for Georgia. There will be no new cold war, he says, as Russia is politically isolated and much weaker than the old Soviet bloc. He says that Georgia can’t defeat Russia with tanks, but that there are two political systems in competition here, and he sees Georgia on the winning side. He believes the appeal of democracy is depriving the undemocratic Russian government of international allies. Russia needs to modernise, he says.

An indication of the distance Russia still has to travel to modernise politically: war trophies on show, and remembering Putin’s first day as president - handing out hunting knives to Russian soldiers in Chechnya.

FIN.

Romulus and Remus illustration from the Times Higher Education Supplement, 1994.

Obelix and Co. copyright © 1976 Goscinny/Uderzo. Translators: Anthea Bell and Derek Hockridge.

No comments:

Post a Comment