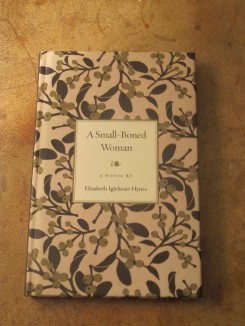

I received a small book for Christmas. Hardback, its cover reminded me of the elegant wallpaper of some Bloomsbury salon: dark green leaves and what might be sloe berries against an ecru background. The book tells the story of a girl called Sally Waite, the precocious daughter of a well-off Southern couple, whom we first meet as an eleven year-old girl, and follow her until, pregnant by her Yankee husband, Kevin, she leaves Alabama for a life in New York. The book – tantalisingly – leaves off just as Sally’s hero, Henry Rountree, an upright local lawyer and friend of the Waite family, has confessed his love for her. We know what happens, though, because Sally is – more or less – my grandmother, Elizabeth Igleheart Hynes.

The novel’s manuscript was found in a drawer by my grandfather when he was going through the possessions of his wife, my grandmother, who died in December 2008. My grandfather and my Aunt Jo spent a year sorting through the various drafts, forming the text into a coherent narrative whilst always keeping faithful to the words my grandmother used. They had the book printed – by the ‘Morgan Women Press’ (Morgan was one of my grandmother’s family names) – and distributed as presents almost two years to the day after my Granny Liz’s funeral. The novel bears a short preface and a postscript – the former explaining the origins of the book, the latter recounting a trip we made to the Birmingham, Alabama neighbourhood in which my grandmother lived. My grandfather writes: “After the funeral, a group of family mourners drove across town to Norwood, the neighborhood where she grew up, to pay a last visit to the family home. All of Norwood was gone: where there had been houses and apartment buildings and little stores there were only weed-grown lots and rubble, with here and there the derelict shell of a big house still standing, uninhabited and unpainted, staring at the wasteland around it through broken windows.” It was indeed like something out of The Wire: menacing youths glared at us from street corners under the brims of their baseball caps, cars slowed to look at us – suited, sombre – as they passed. But, somehow, the spirit of the girl who had lived there so many years ago was with us, and we felt invulnerable because, despite the decay, her presence was in the stones upon which we walked.

The book is beautifully written. Reminding me most of Eudora Welty, it captures with extraordinary clarity something very difficult – a happy youth – and revels in a very particular form of Southern nostalgia. A Small-Boned Woman is the opposite of a misery memoir. This is not to say that it doesn’t deal with weighty issues – racial tension bubbles beneath the surface with occasional violent eruptions. When Sally hears Orrin Butts, a local wheeler-dealer looking for political advancement, reeling off racist cant, she feels “the same sense of unreality I had felt once when I saw a man smashed in a car accident, and expected him to get out of his grotesque, twisted position and walk away whole.” The novel sings with hope, though. Problems, it tells us, can be resolved by intelligent people working together. There is no evil that cannot be beaten through education, discussion and a good Southern sense of fair play.

Whilst Kevin, the Yankee husband, hardly features in the novel, we see Sally’s joy when he returns safe from the war, her excitement at the prospect of their life together in New York. It makes for an extraordinary stereoscopic history when this fictionalised account of my grandparents’ early life together is read alongside my grandfather’s war memoir, Flights of Passage. Just as, I am told, jewellers know when they set stones whether the ring will last, simply from their sense of the integrity of that initial setting, my grandparents’ more than sixty years of happy marriage is unsurprising when you read of the love they felt, all those years ago, as the war ended and their lives began.

It is the beginning of the book that I keep coming back to, though. Sally and her best friend Anna go to Mobile Bay for their summer holidays. It’s an exquisite piece of writing, wonderfully conjouring up the endlessness of those surf-tossed days. I was reminded of my own version of Mobile Bay – a stilted house on North Carolina’s Outer Banks where we’d go with my grandparents and my aunt and uncle and I’d walk along the tide-line looking for jellyfish and shells and then throw myself down on the hot, damp sand. Sally recalls one morning in Mobile Bay like this: “The whole morning we stayed in the blue bay water, sometimes stretching out on the weathered boards of the wharf. A big beam had floated in on the tide, and we played it was a boat. We pushed it out past the boathouse, holding it with our arms and paddling our feet. Then we got astride it, letting the gentle waves propel us to shore.”

It was an extraordinarily moving experience to read the book. My granny’s soft, Southern voice sings on every page. It was, for a moment, like having her back. It is now difficult to unravel the twines of conflicting emotions that the novel has inspired in me. Firstly, a reader’s dissatisfaction at an unfinished book. For I spent two days in the sunny company of Sally Waite and – more importantly – my granny who whispers through and around Sally. Then a kind of sadness that such a good novel was abandoned – I presume when children and my grandfather’s successful literary career got in the way of finishing it. Particularly the first section of the book suggests that my grandmother could have been a very fine novelist; certainly A Small-Boned Woman would have been published, I imagine to some success. But then I sorted through photographs of my grandmother taken in Princeton and Hampstead in the last twenty years of her life, and I saw how happy she was, how proud of her family, her husband, and I knew better than to wish changes to the paths of life’s great binomial tree. We have the novel, it is wonderful, it is enough.

My grandfather sent a copy of A Small-Boned Woman to the editor of the Sewanee Review: the first 25 pages of the novel will be published in the journal later this year.

Well said, nephew. It was certainly a labor of love and I’m so glad others are pleased with it. It was at once thrilling and tragic to have my mother’s voice living in my head day-to-day for all that time. I hope she is pleased at the job we’ve done. So are you descended from more writers than you realized!